African women entrepreneurs can overcome the funding gap with targeted support from a new type of gender-focused investors.

29/06/2020

“If you want to change our society, you help a woman to change her life. Then the woman will change the world.” These are the words of Vera Mbongo, who runs a not-for-profit orphanage attached to a for-profit car-wash business in Cameroon. Just like Mbongo, many women do not start talking about money when asked about their motivation for starting a business.

When Albert Kimbu of the University of Surrey and I asked women entrepreneurs in Cameroon what inspired them, they told us about independence and contributing to society: if that leads the business to grow and make a lot of money, that is a bonus.

The women we spoke to provided striking reasons for why they started a business. One said, “The rate of prostitution can be reduced if women are enabled to be more creative.” Another said, “I want to be independent and not just sit at home as a housewife who gets everything from her husband.” Another “did not want to sit idle at home as a housewife and not pursue my childhood dream to be a decorator”.

When asked what benefits they get from their newly acquired independence, apart from generating income, one participant said, “Men now treat women such as myself with some respect. They no longer treat us with scorn and disdain as they used to do in the past.”

These stories reflect a society where cultural norms still favour men. Women see themselves as experiencing discrimination, being less supported in society and having to combine household and business tasks. For Ernestine Ebong, owner of a décor and events management businesses, this can be very demanding.

“I have been in this business for eleven years and have trained many girls who now have their own small décor businesses,” she said. “Currently I have eleven trainees. Parents come to me begging to train and employ their children as if this is a job for illiterates. You end up teaching them everything from sales to customer service and even how to manage the money you give to them as salaries, pay their rents – [you] advise them how to live a healthy life.”

Businesses that are owned by women are often described as ‘survivalist’ in the sense that they are started out of the necessity to cater for the basic needs of the woman and to supplement their household income. They start from a smaller base and either close after a few years or grow at a much slower pace.

Yet when describing their entrepreneurial journeys, women entrepreneurs in the African context talk about business growth aspirations similar to those in other parts of the world . Another study by Kimbu and myself, on Cameroon, describes the slow growth in women’s entrepreneurial journeys.

Consider that of Pauline Mbouh. After completing hotel management studies, she moved to the capital city, Yaoundé, to live with her elder sister in early 2000. “Getting a job in a reputable hotel that matched my ambition was really tough,” she said. “I began to bake and sell home-made meat pies and cakes near the premises of government departments and private organisations during lunchtime. Slowly, I was saving money, benefiting from using my sister’s property and utilities for free. I even recruited my cousin as my first employee.”

Six years later, in 2006 Pauline rented a property as both living space and business site, and registered as a limited company. “I used my savings, got a loan from my sister, delayed rental payment from the landlord and I also benefited from a one-year tax-free incentive from the government for newly registered businesses.”

By 2011 she had opened two restaurants, employed 25 full-time staff, offered in- and outdoors services and was generating an annual revenue of more than 40 million XAF (approx. US$ 67,700). That is not all. “I run a short fee-paying catering course and a monthly home-cooking show on TV. I have established a poultry farm supplying chicken and eggs to the restaurants and other eateries in the city.” She went on to describe her next growth objective as “to create a chain of restaurants across the three largest cities of Cameroon”.

The research evidence is clear. Without adequate financing, women-owned businesses will continue to struggle to survive or will grow at a much slower rate. More specifically, access to a combination of debt, equity, quasi-equity and ‘patient capital’ investments to women-focused ventures is a potential solution to the gender imbalances.

A new source of investment – gender lens investing

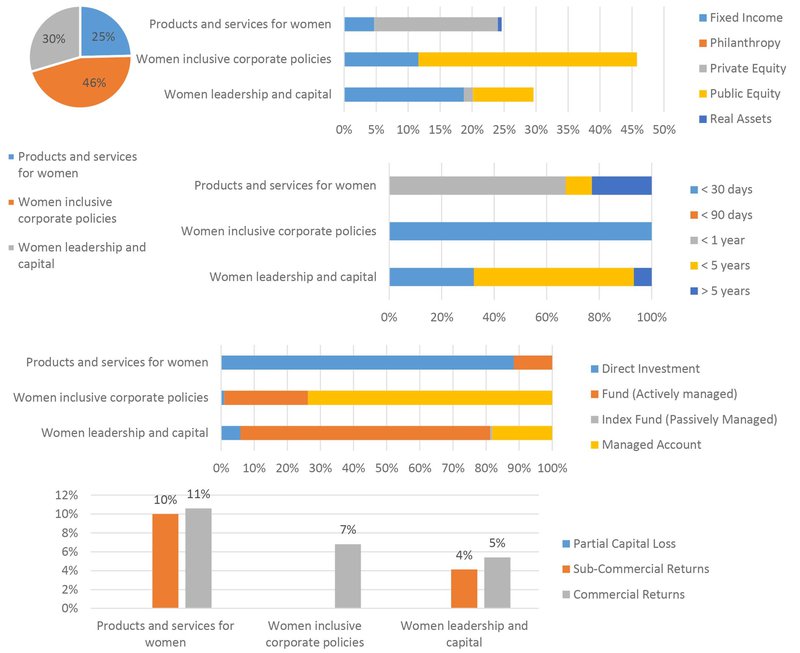

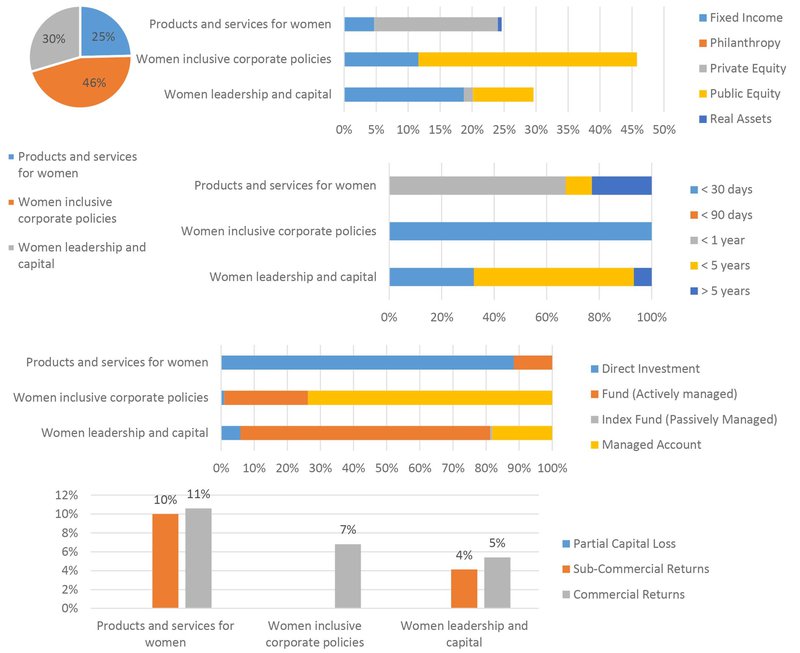

Some investors seek to intentionally and measurably address gender disparities and examine gender dynamics to better inform their investment decisions. This is known as ‘gender lens investing’ (GLI). It takes the form of partnerships between development finance institutions and private venture funds. Together they create pots of money that are then drawn on to invest in businesses related to women: either businesses that women own, or businesses that prioritise employability and retention of female staff, or businesses that sell products for women.

Gender lens investing is a global trend. In 2018, the total publicly available equity and fixed income within GLI was over $2.4 billion and the total capital with a gender lens had reached $2.2 billion. The Global Impact Investing Network – which promotes investment that has a positive social and environmental impact – estimates that at least $12 billion-worth of impact investments were made in sub-Saharan Africa in 2017.

GLI is also growing. A recent survey found that Investments made under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 5 – gender equality – are invreasingly becoming centre stage in the investment strategies of fund managers.

Gender lens investing strategies in Africa

Many financial institutions in African countries have been turning to gender lens investors at country levels. But what does it mean in practice?

Using a gender lens approach to empower women entrepreneurs involves supporting women’s leadership, women’s access to capital, products and services beneficial to women and girls, workplace equity, shareholder engagement and policy work. C-Credit Ltd, a savings and loans cooperative in Cameroon created by and for women, is a typical case. Its primary goals are to provide services that improve the economic and social well-being of women, through a fair rate of interest on savings and loans; and to provide quality financial services that will enable the cooperative to be competitive. Members are rural and semi-urban women entrepreneurs, who are owners and managers of micro- and small businesses in a range of sectors.

For C-Credit, women´s representation in governance and management is automatic: it has a women-focused membership and women-elected board of directors, and equity funding from women-focused investors constituted about 10% of its total assets in 2015.

It has five principles for impact investment: i) C-Credit was created for women; ii) it incorporates savings and loans to promote women´s activities; iii) it offers training on small-scale business project management and record-keeping; iv) it facilitates training for women through community development initiatives; v) it supports the prevention of HIV/AIDS through family-planning advocacy.

C-Credit typifies how GLI can contribute to breaking down gender stereotypes, by extending microcredit and support services to women entrepreneurs. There is a strong focus on access to credit and ad-hoc book-keeping, business and management skills – through group-based lending projects, for instance.

Lukong Mercy, who buys and sells dresses and benefited from C-Credit’s training, explained to me how she gained confidence in growing her business. “I received a text message about a workshop for clients interested in business skills and financial information for growing their business. At the workshop, the local field officer explained how growing our businesses and selling more services can result in us depositing larger sums with C-Credit, which in turn increased how much I was later able to borrow to expand my business further.”

The CEO of C-Credit, Germaine Obili, told me that it was not all about finance and growing the business, however. It is also about breaking cultural barriers that affect the performance of women-owned businesses. “The cultural backgrounds and barriers that we have in our society today hinder many women from getting involved in businesses, no matter how they struggle.

“I have had a group of women whose businesses were doing well but they were still scared of declaring their savings to family members. They tell me to ‘keep it quiet, never allow X to know’.”

A way forward

Those successes suggest ways that could support women’s entrepreneurial journeys. Gender lens investing cannot succeed in African countries without policy support, however. Most national governments provide ad-hoc support to women entrepreneurs and women-owned businesses, but government policies on entrepreneurship are largely gender neutral.

More active public policies could not only promote greater access to finance but also reduce the number of bottlenecks facing women entrepreneurs. These include investing in public infrastructure relevant to women – nursery schools and sanitary facilities, for instance – safe public transportation and internet; reproductive health initiatives; tax incentives; and property legislation that would give women access to collateral security. This support is necessary for finance providers and businesses that are already adopting GLI strategies locally.

Managers of microfinance institutions should adopt frameworks that improve the reporting of evidence and outcomes which are necessary for raising additional capital from gender lens investors. For instance, the Apsen Network of Development Entreneurs provides a framework that disaggregates financial and non-financial performance by gender; the Calvert Foundation provides a framework for advocating change within companies that lack gender diversity and is useful for disaggregating gender representation, for instance in proportion of women owner, managers and employees.

Gender lens investing requires an in-depth understanding of what motivates specific women to become entrepreneurs. It must match those aspirations to the gender lens strategies of investors. Motivations vary among women, but this scrutiny needs to be done to ensure appropriate support for women entrepreneurs who want their businesses to grow and have the largest possible impact on society.

Some of the research reported here comes from ‘Gender Lens Investing in the African Context’ by Richmond Lamptey and myself, in ‘Global Handbook of Impact Investing: Solving Global Problems Via Smarter Capital Markets Towards A More Sustainable Society’, edited by Elsa de Morais Sarmento and R. Paul Herman, due to be published by Wiley in October 2020.

openDemocracy